I grew up on 10 forested acres of land on the side of a mountain on the outskirts of the western North Carolina city of Asheville. My parents built our house overlooking Haw Creek Valley and the Blue Ridge Parkway. Our nearest neighbor was a third of a mile through the woods.

My father believed that children often reacted to their parents’ generation by choosing situations 180 degrees from their parents’ generation. He grew up in a row house in the Oxford Circle neighborhood of northeast Philadelphia. It’s safe to say that his dense neighborhood with his primary school, parks, and public transit was diametrically opposed to what he and my mom chose for me to grow up in.

As my wife and I have chosen where to situate our family, we’ve somehow found a middle ground: a hilly, forested neighborhood whose wide streets and bigger lots a mile from downtown Durham, North Carolina, reflect its history as Durham’s first suburb. Now a central Durham neighborhood, we can easily walk or run downtown but we are surrounded by majestic oaks and loblolly pines.

Perhaps as a reaction to my growing up on a car-dependent mountainside, this environment feels like the right balance for me. If my car needs repairs at the auto shop downtown, I can easily ride my bike to pick it up. My wife and I often ride our bikes to Durham Bulls games and shows at the Durham Performing Arts Center. Durham Station, Durham’s transportation hub, is accessible by walking, biking, or bus. My neighborhood gives me a sense of being surrounded by nature while simultaneously not feeling confined to using my car.

**

Last year, I drove a minivan full of elementary-school-aged boys from Durham to a soccer tournament in Charlotte. As we crisscrossed Charlotte between the soccer fields and our hotel, and back again several times, I experienced parts of Charlotte beyond its central business district in Uptown where I normally stay for a business meeting or an event.

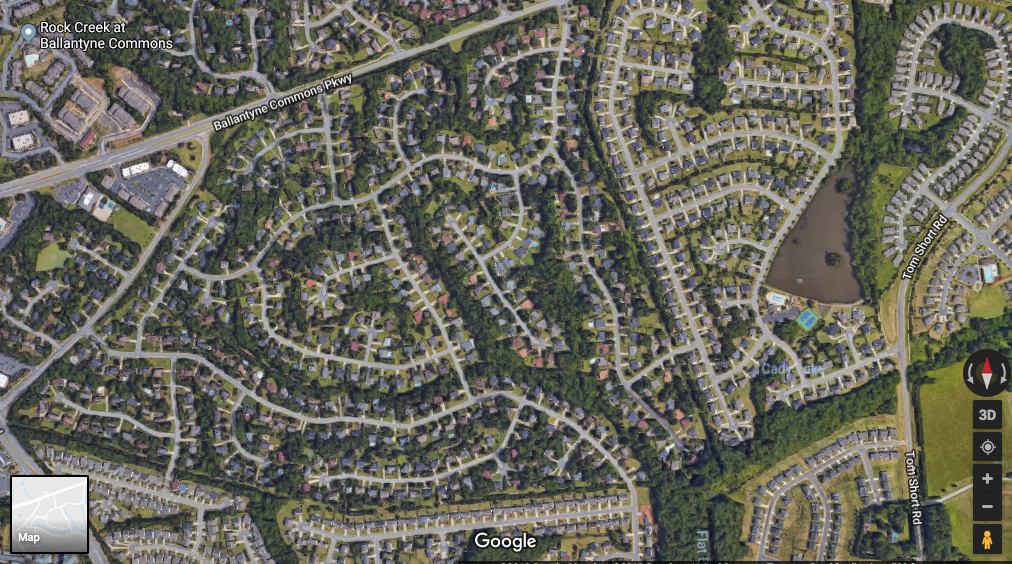

I’ve spent the bulk of my career in the transit industry, so my defining thought as we traversed Charlotte was how incompatible much of Charlotte is to public transit. Wide roads, big neighborhoods, and meandering streets are all barriers that impede transit ridership.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that public transit can’t do good work in Charlotte, or that its current system is run poorly (though they are losing ridership). But it does mean that public transit faces hurdles to be successful in Charlotte that my father’s dense neighborhood in Philadelphia never faced. As transit planner (and recent The Movement Podcast guest!) Christof Spieler noted recently in a profile of his new book on public transit, “When we look at the success of transit systems, we’re not just seeing transit decisions. We’re seeing land use decisions,” Spieler says. “How are people distributed? How are jobs distributed?”

Perhaps it was just my particular expeditions across the southern part of Charlotte, but what I saw was big neighborhood after big neighborhood behind big walls, requiring a vehicle of considerable size to access them. Big neighborhoods combined with a single-use (housing) means residents can’t just leave their homes to walk a couple of blocks to access retail or jobs. Neighborhoods had distances of at least a half mile just to get to the main road, with access to amenities like grocery stores and restaurants even farther away, reinforcing the car-dependent culture.

A few miles north, Charlotte’s dense Uptown has seen riders use a proliferation of scooters to go about a mile on average. For many of the neighborhoods I passed, a mile on a dockless bike or scooter might not even get a user out of the neighborhood, let alone to a local coffee shop or grocery store. And considering that nearly half of all trips in the US are less than three miles, that’s troubling.

**

Construction began on Interstate 485 in 1988 and took 27 years to complete its 67- mile ring around Charlotte. But a funny thing happened on the way to pavement paradise: induced demand. Turns out a brand new and uncongested highway is really attractive to new residents and development. That increased demand makes that newly opened highway congested. Sometimes this happens quickly and sometimes it takes a while. In Charlotte’s case, I-485 wasn’t even complete before some of the older sections were already exceeding their scheduled capacity.

Along with the northern part of Charlotte that is also served by I-485, the southern part of Charlotte, near my son’s tournament, has seen most of Charlotte’s growth since 2010. Growth doesn’t happen by accident. Governments set policies (including zoning and financial incentives) that dictate where growth happens. These land-use decisions all have impacts. And those impacts tend to be long-term in nature.

I empathize with these past and current leaders. When people are relocating to an attractive city like Charlotte with good jobs and schools, elected officials hear the cries about traffic and want to do something about it. They build roads, and those roads provide a release valve for increased congestion, and then induced demand fills them back up, creating a Sisyphean version of transportation policy.

**

Where do we go from here?

I realized as I was driving through the southern part of Charlotte – with the big neighborhoods and retail segregated from housing – that nothing could change until people decide they don’t want to live in that environment anymore. Is that likely to happen? There are certainly signs that people are moving back to cities, but what that actually looks like will likely depend on the city. Most areas around I-485 are within Charlotte city limits, but they feel significantly different than where my dad grew up in Philadelphia or even some of the Charlotte neighborhoods closer to Uptown. Both are in the city proper, but feel completely different.

The Uptown area of Charlotte is clearly growing. And development in an area that is as dense as Uptown with access to more space efficient modes of transit like light rail, buses, bikes, and scooters makes good planning sense. But what comes first? When one of the 40 plus people a day moves to Charlotte, do they move to where the youngest housing stock is on the gigantic interstate ringing the city? Or do they move to the Uptown area, even if much of it is still being built? It creates a chicken and egg dilemma for Charlotte to figure out what comes first: the development plan or the people? Do the people force the development plan or does the development plan force the people?

This chicken and egg problem highlights the second way we can move forward: Courage by our elected officials to make long-term choices. Courage to reject annexation and its short-term promise of tax base (and increased congestion). Courage to overrule NIMBYs who don’t want denser urban development. Courage to encourage more mixed-use developments where a walk or quick scooter ride can get you to that local coffee shop. To be fair, Charlotte pushed forward on a long-term investment in light rail in the 1980s and 1990s but the development patterns are hard to overcome.

**

Reflecting on the stately trees that surround my mountainside childhood home in Asheville, and my current home in central Durham, as well as my recent trip through some of Charlotte’s newest neighborhoods – with much fewer, smaller, and younger trees – I recall the Chinese proverb, “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The next best time is today.”

While there are certainly short-term benefits to planting a tree, the act is, fundamentally, a long-term investment. And if today’s leaders can’t plant trees today so that future generations can enjoy the shade, we all face a hot, sticky future.

Contact us to talk to an expert about TransLoc’s mobility solutions!